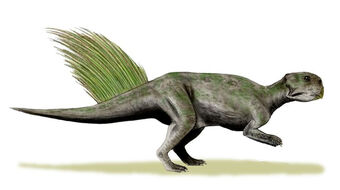

Restoration of P. mongoliensis, showing tail bristles

Psittacosaurus ("parrot lizard") is a primitive ceratopsian dinosaur of Early Cretaceous Asia. The genus itself contains the most species of any known dinosaur genus.

Description[]

The different species of Psittacosaurus varied in size and some skeletal structures, but retained the same general body shape. The most well-known species, P. mongoliensis, grew to two meters in length[1] and weighed over 20 kilograms.[2] The other species were generally slightly smaller or larger than this.[3]

Psittacosaurus was a type of primitive ceratopsian, but it was bipedal instead of quadrupedal and lacked both horns and a frill.[4] Its skull was very tall in height and short in length, and depending on the species appeared almost round. Both jaws sported a large beak, and the skull possessed extended cheek bones. The rest of the body, however, was similar to that of other bipedal ornithischians.[4]

At least one species of Psittacosaurus also possessed bristles on the tail (see Integument, below).

Classification[]

Life reconstructions of eight species of Psittacosaurus. The species on the uppermost right, P. major, is now regarded as a synonym of P. lujiatunensis.

Psittacosaurus is the type genus of the family Psittacosauridae.[5] Psittacosaurids were basal to all known ceratopsians, with the exception of one or two species.[6]

Species[]

Seventeen species of Psittacosaurus have been named overall, although only nine to eleven remain in use today.[7] The species are determined from differences in their skulls and location.

This is a list of currently valid species of Psittacosaurus:

- Psittacosaurus mongoliensis - found in Mongolia and northern China[8]

- Psittacosaurus sinensis - found in northeastern China[9]

- Psittacosaurus meileyingensis - found in north-central China[10]

- Psittacosaurus xinjiangensis - found in northwestern China[11]

- Psittacosaurus neimongoliensis - found in north-central China[12]

- Psittacosaurus ordosensis - found in north-central China[12]

- Psittacosaurus mazongshanensis - found in northwestern China[13]

- Psittacosaurus sibiricus - found in Russia (southern Siberia)[14]

- Psittacosaurus lujiatunensis - found in northeastern China[15]

- Psittacosaurus gobiensis - found in Inner Mongolia[16]

Psittacosaurus sattayaraki is a possible species.[17] Many specimens of the genus remain unidentified at the species level, and are colloquially referred to as Psittacosaurus sp.

The following cladogram of Psittacosaurus is based on a study by Paul Sereno in 2010:[18]

| Psittacosaurus |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History[]

The type species of Psittacosaurus, P. mongoliensis, was described in 1923 by Henry Fairfield Osborn. Its translated genus name, "parrot lizard", refers to the animal's parrot-like beak.[19] Since then, specimens from the genus have been discovered from Siberia to China, and possibly as far south as Thailand. The oldest, and likely most basal, species is P. lujiatunensis of the Yixian Formation of China.[15]

Paleobiology[]

Diet[]

Unlike later ceratopsians, Psittacosaurus did not have teeth suitable for chewing or grinding food. Instead, they used gastroliths to wear down plant matter.[1]

The large beak of Psittacosaurus may have been well-suited for cracking open nuts and seeds.[16]

Integument[]

The specimen of Psittacosaurus showing tail bristles, housed at the Senckenberg Museum

A well-preserved specimen of Psittacosaurus sp. examined in 2002 (which most likely came from the Yixian Formation) exhibits integumentary features previously unknown in ceratopsians. Most of the body is covered with scales, much like other ceratopsians, but a row of hollow bristles is preserved running down the dorsal surface of the animal's tail. These bristles measured approximately 16 centimeters in length each. It is possible that the bristles may have been used for display purposes.[20] The specimen currently resides at the Senckenberg Museum in Germany.

Growth rate[]

Several juvenile specimens of Psittacosaurus have been found. Hatchlings could measure as small as 11 to 13 centimeters in length, with skulls only 3 centimeters or so in length.[21]

A histological examination of P. mongoliensis conducted in 2000 determined the growth rate of the species. The smallest specimens were believed to be three years old and estimated at less than 1 kilogram in wight, while the largest specimens were believed to be nine years old and estimated at nearly 20 kilograms in weight. This is rapid growth compared to most reptiles, but slower than that of modern birds and placental mammals. The examination suggested that Psittacosaurus lived 10 to 11 years.[2]

Possible aquatic behavior[]

Tracy Ford and Larry Martin proposed in 2010 that at least some species of Psittacosaurus may have led a semi-aquatic lifestyle. They based their interpretation off of details such as the orientation of the eyes and nostrils, possible limb motion, the presence of gastroliths (possibly used as ballast), and the lake depositional setting of many specimens.[22]

References[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sereno, Paul C. (1997). Psittacosauridae. In: Currie, Philip J. & Padian, Kevin P. (Eds.). The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. San Diego: Academic Press. Pp. 611–613.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Erickson, Gregory M. & Tumanova, Tatyana A. (2000). Growth curve of Psittacosaurus mongoliensis Osborn (Ceratopsia: Psittacosauridae) inferred from long bone histology. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 130: 551–566.

- ↑ Brinkman, Donald B., Eberth, David A., Ryan, M.J. & Chen Peiji. (2001). The occurrence of Psittacosaurus xinjiangensis Sereno and Chao, 1988 in the Urho area, Junggar basin, Xinjiang. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 38: 1781–1786.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 You Hailu & Dodson, Peter. (2004). Basal Ceratopsia. In: Weishampel, David B., Dodson, Peter, & Osmolska, Halszka (Eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd Edition). Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 478–493.

- ↑ You Hailu, Xu Xing & Wang Xiaolin. (2003). A new genus of Psittacosauridae (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) and the origin and early evolution of marginocephalian dinosaurs. Acta Geologica Sinica (English edition) 77(1): 15–20.

- ↑ Xu Xing, Forster, Catherine A., Clark, James M. & Mo Jinyou. (2006). A basal ceratopsian with transitional features from the Late Jurassic of northwestern China. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London: Biological Sciences. 273: 2135–2140. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3566

- ↑ Sereno, Paul C, Zhao Xijin, Brown, Loren & Tan Lin. (2007). New psittacosaurid highlights skull enlargement in horned dinosaurs. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 52(2): 275–284.

- ↑ Sereno, Paul C. (1990). New data on parrot-beaked dinosaurs (Psittacosaurus). In: Carpenter, Ken & Currie, Philip J. (Eds.). Dinosaur Systematics: Perspectives and Approaches. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 203–210.

- ↑ Young, C.C. (1958). The dinosaur remains of Laiyang, Shantung. Palaeontologia Sinica Series C 16: 53–159.

- ↑ Sereno, Paul C., Zhao Xijin, Chang Zhengwu & Rao Chenggang. (1988). Psittacosaurus meileyingensis (Ornithischia: Ceratopsia), a new psittacosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of northeastern China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 8: 366–377.

- ↑ Sereno, Paul C. & Zhao Xijin. (1988). Psittacosaurus xinjiangensis (Ornithischia: Ceratopsia), a new psittacosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of northwestern China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 8: 353–365.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Russell, Dale A. & Zhao Xijin. (1996). New psittacosaur occurrences in Inner Mongolia. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 33: 637–648.

- ↑ Xu Xing. (1997). A new psittacosaur (Psittacosaurus mazongshanensis sp. nov.) from Mazongshan area, Gansu Province, China. In: Dong Z. (Ed.). Sino-Japanese Silk Road Dinosaur Expedition. Beijing: China Ocean Press. Pp. 48–67.

- ↑ Averianov, Alexander O., Voronkevich, Alexei V., Leshchinskiy, Sergei V. & Fayngertz, Alexei V. (2006). A ceratopsian dinosaur Psittacosaurus sibiricus from the Early Cretaceous of West Siberia, Russia and its phylogenetic relationships. Journal of Systematic Paleontology 4(4): 359–395.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Zhou Changfu, Gao Keqin, Fox, Richard C. & Chen Shuihua. (2006). A new species of Psittacosaurus (Dinosauria: Ceratopsia) from the Early Cretaceous Yixian Formation, Liaoning, China. Palaeoworld 15: 100–114.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Sereno, Paul C., Zhao Xijin, Tan Lin. (2010). A new psittacosaur from Inner Mongolia and the parrot-like structure and function of the psittacosaur skull. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 277(1679):199–209.

- ↑ Buffetaut, Eric & Suteethorn, Varavudh. (2002). Remarks on Psittacosaurus sattayaraki Buffetaut & Suteethorn, 1992, a ceratopsian dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Thailand. Oryctos 4: 71–73.

- ↑ Sereno, Paul C. (2010). Taxonomy, cranial morphology, and relationships of parrot-beaked dinosaurs (Ceratopsia:Psittacosaurus). In: Ryan, Michael J., Chinnery-Allgeier, Brenda J. & Eberth, David A. (Eds.). New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. Pp. 21–58.

- ↑ Osborn, Henry F. (1923). Two Lower Cretaceous dinosaurs of Mongolia. American Museum Novitates 95: 1–10.

- ↑ Mayr, Gerald, Peters, D. Stephan, Plodowski, Gerhard & Vogel, Olaf. (2002). Bristle-like integumentary structures at the tail of the horned dinosaur Psittacosaurus. Naturwissenschaften 89: 361–365.

- ↑ Coombs, Walter P. (1982). Juvenile specimens of the ornithischian dinosaur Psittacosaurus. Palaeontology 25: 89–107.

- ↑ Ford, Tracy L.; and Martin, Larry D. (2010). "A semi-aquatic life habit for Psittacosaurus". In Ryan, Michael J.; Chinnery-Allgeier, Brenda J.; and Eberth, David A. (editors.). New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 328–339. ISBN 978-0-253-35358-0.